The Cold Fusion Saga: From Breakthrough to Banishment

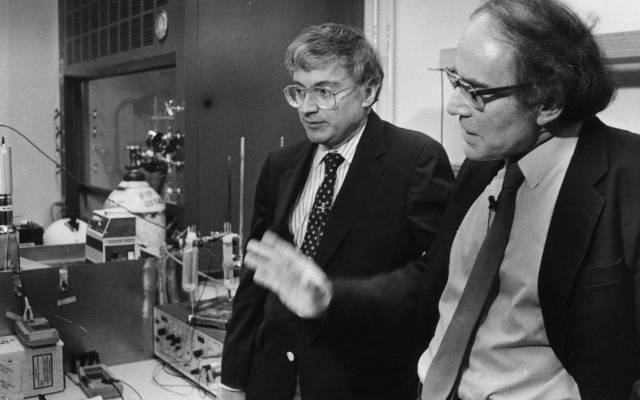

Martin Fleischman and Stanley Pons

By EVWorld Si Editorial Team

What Fleischmann and Pons Claimed

On March 23, 1989, electrochemists Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons held a press conference at the University of Utah announcing they had achieved nuclear fusion at room temperature. Their setup was deceptively simple: they used electrolysis to force deuterium (heavy hydrogen) into a palladium cathode immersed in heavy water (D2O).

Their observations:

- Excess heat production that couldn't be explained by chemical reactions

- Detection of neutron radiation

- Production of tritium (a hydrogen isotope)

- Gamma ray emissions

- Nuclear byproducts like helium-4

Their proposed mechanism:

Fleischmann and Pons theorized that the palladium lattice could compress deuterium nuclei to such high densities that they would overcome the Coulomb barrier (the electrical repulsion between positively charged nuclei) and fuse at room temperature. They suggested the metal lattice created a unique environment that screened or reduced the electrical repulsion, allowing fusion to occur without the extreme temperatures (100+ million degrees) required in conventional fusion.

Why the Scientific Community Rejected It

The rejection was swift and harsh for several compelling reasons:

1. Theoretical Impossibility:

The Coulomb barrier requires enormous energy to overcome. Conventional physics showed that room temperature simply couldn't provide enough energy for deuterium nuclei to get close enough to fuse.

2. Inconsistent Nuclear Signatures:

If fusion were occurring at the claimed rates, the experiment should have produced lethal amounts of neutron radiation and gamma rays. The detected levels were far too low and inconsistent.

3. Replication Failures:

Most laboratories worldwide failed to reproduce the results. When some detected excess heat, they couldn't detect the expected nuclear byproducts, and vice versa.

4. Poor Experimental Controls:

Critics noted inadequate calorimetry (heat measurement), potential chemical contamination, and measurement errors that could explain the "anomalous" results.

5. Bypassed Peer Review:

Announcing results at a press conference before peer review violated scientific protocol and raised red flags about the quality of their work.

6. Scale Problems:

The amount of fusion needed to produce the observed heat should have generated obvious nuclear radiation and byproducts that simply weren't there in sufficient quantities.

Replication Attempts Over the Decades

Despite mainstream rejection, research continued in what became known as "Low Energy Nuclear Reactions" (LENR) or "Electrochemically Assisted Nuclear Reactions" (EANR):

Early Replication Efforts (1989-1991):

- Hundreds of labs worldwide attempted replication

- Some reported positive results (excess heat), others found nothing

- Notable failures included prestigious institutions like MIT, Caltech, and Harwell Laboratory in the UK

Persistent Research Groups:

- SRI International (California) - Conducted extensive studies funded by various agencies

- NASA Glenn Research Center - Maintained an active LENR research program

- Naval Research Laboratory - Published positive results in peer-reviewed journals

- ENEA (Italian National Agency) - Claimed successful replications

- Toyota - Reported detecting nuclear byproducts in nickel-hydrogen experiments

- Industrial researchers including companies like Brillouin Energy and E-Cat

International Conferences:

- International Conference on Cold Fusion (ICCF) has met regularly since 1990

- Researchers from major institutions continue presenting results

- Japan, Italy, Russia, and other countries maintained government-funded programs

Recent Developments:

- Google's replication attempt (2019) - Well-funded, rigorous study found no evidence of anomalous effects

- NASA's continued interest - Still lists LENR as a potential breakthrough technology

- U.S. Navy funding - Has supported research claiming positive results

The Ongoing Controversy

The field remains deeply polarized. Proponents argue that:

- Some experiments do show reproducible anomalous effects

- New theoretical models might explain how LENR could work

- Industrial applications are being developed despite skepticism

Skeptics maintain that:

- No convincing demonstration of nuclear processes has been shown

- Excess heat claims remain unsubstantiated or attributable to experimental error

- The theoretical barriers remain insurmountable

The story illustrates how extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and how the scientific process—while sometimes harsh—serves to protect against false breakthroughs that could waste resources and mislead research directions. However, it also shows how some researchers persist in pursuing controversial ideas, occasionally leading to unexpected discoveries even when the original hypothesis proves incorrect.

Sources and Further Reading:

- Britannica: Cold Fusion

- American Physical Society: This Month in Physics History - Cold Fusion

- Nature: Google attempts to replicate famous cold-fusion experiment

- NASA: Low Energy Nuclear Reactions

- ScienceDirect: Electrochemically induced nuclear fusion of deuterium

- LENR-CANR: Cold Fusion Research Library

- International Conference on Cold Fusion (ICCF)

- Naval Research Laboratory: New Insights on Electrochemical Cells

Original Backlink

Views: 1693

Articles featured here are generated by supervised Synthetic Intelligence (AKA "Artificial Intelligence").